Space colonization is a hot topic in the 21st century, and most of the world can’t wait for the chance to jump aboard a spaceship and fly to extraterrestrial human colonies. Here’s a look at the various ways we can colonize space, and the looming reasons why we should.

Mankind has always been fascinated by the great beyond — the desire to explore it, the desire to investigate it, and, as the technological advancement of humankind approaches its zenith, the desire to inhabit it!

Through the ages, countless scientists have tried to make some sense of the endless expanse that shelters us. Some, such as Copernicus and Galileo, braved religious persecution to stand up for the scientific truth, whereas some, such as Isaac Newton, changed our understanding of the mechanics of planetary motion forever. However, it’s fairly safe to say that not one of them, not even the Galileos and the Newtons, had envisioned a 21st century where not just exploring the universe but actually colonizing it is a very much achievable milestone.

In the modern world, pampered by iconic sci-fi and dramatic advancement in space research, one would struggle to find someone actually rejecting the idea of colonizing space. Living in space is a lure hard to refuse for scientists and romantics alike, and considering the effects of overpopulation on the Earth, relocation would probably be quite beneficial for all parties concerned.

Space technology has undergone drastic advancements in the last two decades, and the ease with which the International Space Station was built, coupled with the sheer number of artificial satellites now circling the Earth, certainly makes an irrefutable claim that in time, we indeed can inhabit space.

But before you play the Star Trek theme music in your mind, let’s take a look at how humankind can populate the vast expanses of space, and compare where each method scores and loses out at the present stage of technological advancement.

How Can We Do It?

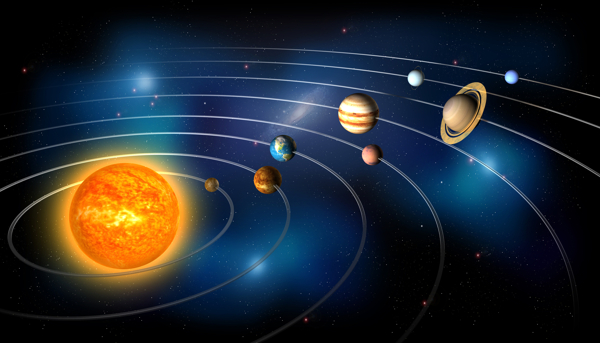

The most practicable modes of colonizing space are colonizing celestial bodies close to the Earth, such as Mars or our own moon, colonizing large crafts in Earth orbit, or in other words, establishing colonies in large space stations, and a climatic engineering technique known as terraforming. There are obvious advantages and disadvantages to these methods.

Inhabiting Other Celestial Bodies

This appears to be the simplest solution, but there is an inherent drawback to this plan. Earth is the only known planet that supports life, and there’s a quite simple reason to it. Every solar system has an area called the circumstellar habitable zone, which literally means the area around a star that can be inhabited. The Earth supports life because it is in the habitable zone around its sun. If the Earth had been a bit closer to the Sun, it would have suffered the same fate as Venus and become a hot, inhospitable region. On the other hand, if the Earth had been a bit farther from the Sun, it would not have received enough warmth to sustain life as we know it.

Even though planets have been discovered in the habitable zones of other solar systems, it would take hundreds of generations for a human colony to simply reach those planets. So barring the development of Star Trek-esque technology in the next few centuries, we are confined to our own solar system.

So we still have SEVEN other planets to play with, right?

Unfortunately, though we share our sun with seven other planets, six of them clearly lie outside the habitable zone. Mercury is too close to the Sun, and is therefore Hot with a capital H — more than 420 °C (788 °F); Venus’ toxic atmosphere creates the strongest greenhouse effect in the solar system, making Venus even hotter than Mercury — more than 460 °C (860 °F); and Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are made of gases, and are therefore impossible to inhabit.

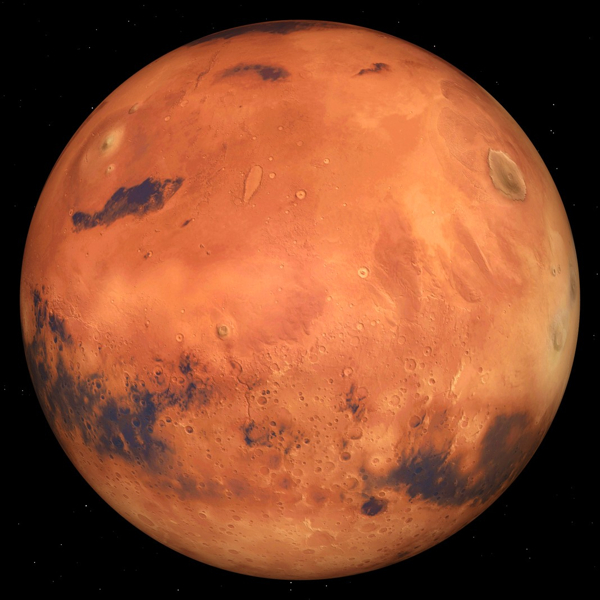

► Mars is the only other planet in our solar system that could support human life.

However, Mars is frigid and presently supports no life. It would take a herculean effort to transport all the material required to build a colony on Mars (but not impossible, considering the ease with which the Spirit, Opportunity and Curiosity Mars rover missions were carried out).

Moreover, Mars has a drastically different atmosphere than the Earth, consisting almost entirely of CO2 (95%), nitrogen, and argon, with traces of oxygen and water vapor. The atmosphere is much rarer than the Earth’s, and consequently can’t block solar radiations in the same capacity. The surface of Mars is constantly bombarded by solar radiation, and a huge amount of man-made protection would be needed if a human colony is to be formed. The one advantage Mars holds is that it contains vast amounts of water, albeit in the form of polar ice caps. For life to pan out as we know it on Earth, water is an essential starting point.

► Compared to the Moon, though, Mars is practically a Garden of Eden.

The Moon has virtually no atmosphere at all. There is no protection from solar radiation of any kind, leading to the half facing the Sun becoming extremely hot — more than 120 °C (248 °F) — and the other half becoming extremely cold — less than -170 °C (-274 °F). A massive ‘shield’ would be required just to maintain a thermal equilibrium in the human community, without even mentioning the relentless solar radiation and solar winds.

► Europa, one of Jupiter’s 67 (confirmed) moons, has a surface surprisingly similar to the Earth. Most of its surface is ice and silicate rock, and it is conjectured to have a core made of iron and an underground ocean.

However, there are obvious drawbacks to inhabiting Europa. The main reason is that it is too far from the Sun, and constant heating would be required to sustain a human colony in the way of life practiced on Earth. This problem can be solved through nuclear fusion, which is being extensively researched all over the world, but there’s another, more important problem. Like most moons in the solar system, Europa has practically no atmosphere, and dramatically advanced technologies would have to be developed and inculcated in our daily lives to provide the composition of air necessary for human survival.

► Exoplanets, or extrasolar planets are a highly attractive but highly improbable destination, at least in the next few millennia. Exoplanets are planets in other solar systems. 26 planets have thus far been found to have a high potential for future human colonization.

Many of these planets have indeed been observed to have Earth-like dimensions, and some have even been found to have Earth-like atmospheric conditions. This may seem like a lucrative proposition, but even the nearest exoplanet, the Alpha Centauri Bb, lies 4.3 light years away from the Earth. Without drastically advanced spacecrafts, humans would have to pass through thousands of generations before they reached Alpha Centauri Bb. And what’s more, although Alpha Centauri Bb is the nearest non-gas-giant exoplanet, it is, like Mercury or Venus, situated too close to its sun, Alpha Centauri B, and is thus too hot for habitation.

The nearest possibly habitable exoplanets, Tau Ceti e and Tau Ceti f, lie close to 12 light years away — about three times the distance to Alpha Centauri Bb. Moreover, these two planets in the Tau Ceti solar system are yet unconfirmed, and their habitability is merely an educated guess.

Terraforming

Terraforming, or planetary engineering is a proposed method of deliberately altering another planet’s atmosphere, and thus its terrain and ecology, to make it similar to that of the Earth’s. Famous astronomer Carl Sagan first proposed terraforming Venus and Mars. The proposed process of terraforming Venus fell apart due to the planet’s incredibly thick and toxic atmosphere, but the idea of transforming Mars to resemble the Earth has persisted.

In fact, engineering Mars to our liking is to a considerable degree achievable with current technology. Increasing the concentration of greenhouse gases on Mars, either by sublimating those already present on its surface as ice or importing them from other planets and moons, is the first step in a long process. Although Martian atmosphere contains 95% CO2, it is so thin that the maximum atmospheric density on Mars can only be seen on the Earth at a height of 35 km — 4 times the height of Mt. Everest!

The terraforming process would gradually involve the introduction of hydrogen and methane, which would react with the iron oxides on Mars to produce water, which could then be used as a base for aquatic life.

The most prominent drawbacks to this admirable theory is the inability of any space agency in the world to fund such an ambitious, time-consuming, and risky process. Technologically, space research is still some rungs below what is ideally needed for this project. Chemically, an almost insurmountable obstacle is the difficulty in obtaining a sufficient amount of a heavy inactive gas, such as nitrogen, or argon, to provide the buffer gas (like nitrogen, which is 78% of the air on Earth) to the restructured Martian atmosphere.

There is Hope for Intergalactic Travel

Even if traveling to planets in other solar systems is a virtual impossibility in the next few centuries, there is no limit to the human genius. Ideas that seem impossible are brought to life in the blink of an eye, and dreams condemned to remain just that are realized in matters of moments. For the neanderthal man, smelting and using metals was a thought apparently beyond the realms of possibility. For the modern, intelligent human, intergalactic travel is similarly apparently impossible.

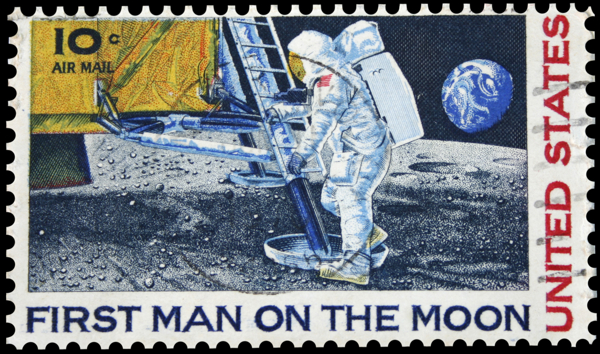

So what if we can’t get a man beyond the solar system? Just 50 years ago, we couldn’t get a man on the Moon! Just 60 years ago, we couldn’t get a man in space! Just 125 years ago, we couldn’t fly, imagine such a time! Given the exemplary rate at which we have conquered the first few hurdles in space research and exploration, it is but natural to expect — rather than hope — that we would, in due time, develop what is needed to save ourselves from inevitable doom.

Inhabiting a Space Station In Earth Orbit

Inhabiting other planets and our friendly neighborhood, the Moon, requires quite a lot of progress in space science and aeronautical technology. Until that is achieved, and probably even afterwards, Space stations appear to be the best alternative.

Nine space stations, including the International Space Station, have already been constructed and deployed in Earth orbit. This technology has the clear advantage of being one in vogue in the present global aeronautical scenario, and is being researched to maximize its efficiency. Even at the current rate, it won’t take more than a century to design and build a space station large enough to house substantial (in terms of millions) human population.

This method has several clear advantages, besides being one that is being researched and bettered as we speak. Since space stations remain in low Earth orbit (less than 2000 km from the surface of the Earth), periodically transporting essential resources would be much easier than to colonies on other planets. Also, like in the space stations deployed at present, solar energy would provide an endless supply of power, virtually eliminating the need for earthbound power sources.

Why Should We Do It?

Overpopulation

The land on Earth is more than enough to ‘contain’ hundreds of our new generations. However, the carrying capacity of the Earth, which is, in simple terms, the maximum human population that can be raised on the planet in acceptable conditions, is now being stretched to unprecedented limits.

One of the most important resources in the modern world is petroleum. On Earth, humans consume thousands of tons of petroleum every year. In low earth orbit though, petroleum could be completely replaced by solar energy and nuclear fusion. This would leave a reservoir of oil for the earthbound population, and extend the expiration date on the precious resource by hundreds of years.

Similarly, if extraterrestrial colonies could be built with native materials, it would make the colonies virtually self-sufficient, bar food.

Expansion of the Sun

All stars go through the process of stellar evolution, the life cycle of stars.

According to the Sun’s current stage in this cycle, it is expected to grow in volume and temperature in a few billion years — predictions vary from 1 billion to 5 billion years. For a measure of scale, the lowest prediction of 1 billion years is roughly equal to the time that has passed since the first multicellular life forms evolved on Earth!

Granted, this is not a problem we, or millions of our future generations would have to face in our lifetimes, but the effects of the Sun’s expansion on Earth are expected to begin much earlier than that. The best illustration of the threats posed to the Earth by solar expansion is the present form of the planet Venus. Venus is believed to have had vast oceans of water and a much more habitable environment in the past. But due to an increase in the Sun’s temperature, the oceans vaporized, causing runaway greenhouse effect, and eventually turning Venus into the hot, barren land that it is today.

Since space stations in low Earth orbit would not be able to survive this scenario, interstellar travel needs to be researched and perfected before this calamity inevitably occurs. Fortunately, the long-drawn time scale of stellar evolution has given us oodles of time that must be spent peeping into the internal affairs of other solar systems.

Because We CAN!

Do we really need another reason? When we discovered that we could hunt much better and live better lives by walking on two feet instead of four, did we crawl back to our caves and forget about it? When we discovered that wheels made carrying stuff — dead animals, rocks, or what have you — much easier, did we reject that notion and drag ourselves to mediocrity? When we saw that birds could fly, did we ignore it and try to repress the memory? When we discovered we could send a man to the Moon, did we laugh it off as a lunatic’s dream?

NO! A wholehearted, resounding, primeval no!

It’s a basal human desire to boldly go where no man has gone before. To not progress along the path when we know the way and have the tools to counter the thickets is taking a step backward, and irrespective of all other arguments, is not the way humans were designed.

Why Now?

The Earth’s resources are being stretched close to breaking point, while the inevitable expansion of human civilization has endangered virtually every other animal on the face of the planet. In addition to man’s adverse influence on the planet, the planet itself is staring down the barrel of inevitable doom when the Sun finally begins the next stage in its life. Mankind can and must migrate — according to none other than venerated physicist Stephen Hawking — to extraterrestrial colonies to ease the pressure on our home planet. If that is to be considered axiomatic, the most obvious question would be,

WHY, when we had sent man into space in 1961 and on the Moon in 1969, did space colonization take more than 40 years after Yuri Gagarin’s epochal flight to become a topic discussed in sincerity?

The answer to that question is deeply intertwined in the global political and economic trends across the second half of the 20th century.

The Space Age was ushered in the 1960s upon a world largely unprepared for such a massive technological leap. The coming of the Space Age, occurring at the height of the Cold War, was hurried, harried, and desperately hastened to claim the all-important first spot in the Space Race — one of the most public subplots of the Cold War.

The early 1960s were all about ‘getting a man in space’, a mission which the Soviet Union accomplished by sending Col. Gagarin in space. The US bagged the next, more significant victory by sending Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins to the Moon. In the late 60s, plans of colonizing what little portion of space humankind had explored were utterly impractical, not least due to the lack of the necessary technology and equipment.

Once the two politically significant milestones had been achieved, the Space Race cooled down a bit, and eventually ran into the troubled American economy of the late 1970s. The financial troubles served to further slow down a slackening space research system already depreciated in the eyes of the masses, who protested the heavy outlay on lunar missions and had become overtly cautious due to the near miss in the notorious Apollo-13 mission. However, the cloud had a silver lining — as the lunar missions were stopped, NASA was given the green light to develop the space shuttle and also launched the Voyager space probes.

While NASA ran into bureaucratic barriers, the Soviet Union (which didn’t have a central, unified space agency like NASA) successfully launched the first space station under the Salyut program.

The Soviet space station missions, some of which lasted around 6 months, were the first human ‘colonies’ in space.

The situation was reversed in the late 1980s, as the Soviet system ran out of funding due to the weakening of the Soviet state, and as the Soviet Union disbanded in 1991, the world was thrown into chaos as it adjusted to the new, unipolar global political hierarchy. In the 1990s, after the dust had begun to settle over the Soviet Union breakdown, the commercial advantages of space technology came to the fore, as countless communication satellites were put into place.

It was only in the 21st century, with the political order in the world somewhat balanced and the commercial avenues of space technology well-established, that space colonization began to develop into something more than hushed whispers.

The Salyut and Skylab space stations, launched in the 1970s by the Soviet Union and the USA respectively, had shown the way forward, but the Russian Mir space station upped the ante in the late 80s and 90s, and in the new millennium, the International Space Station, an iconic symbol of the world’s superpowers coming together to fulfill one common purpose, became the largest man-made structure orbiting the Earth. If the progress in space science continues at the present rate, it is surely a matter of when and not if humans succeed in building the first colony in space.